Arctic killing spree

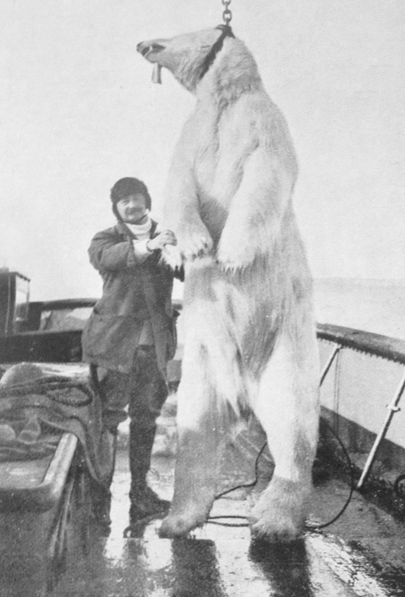

Foreign hunters have impacted several polar bear populations since the 1600s. This image shows the 17th Duke of Medinaceli on his expedition to the North Pole in 1910.

Foreign hunters have impacted several polar bear populations since the 1600s. This image shows the 17th Duke of Medinaceli on his expedition to the North Pole in 1910.

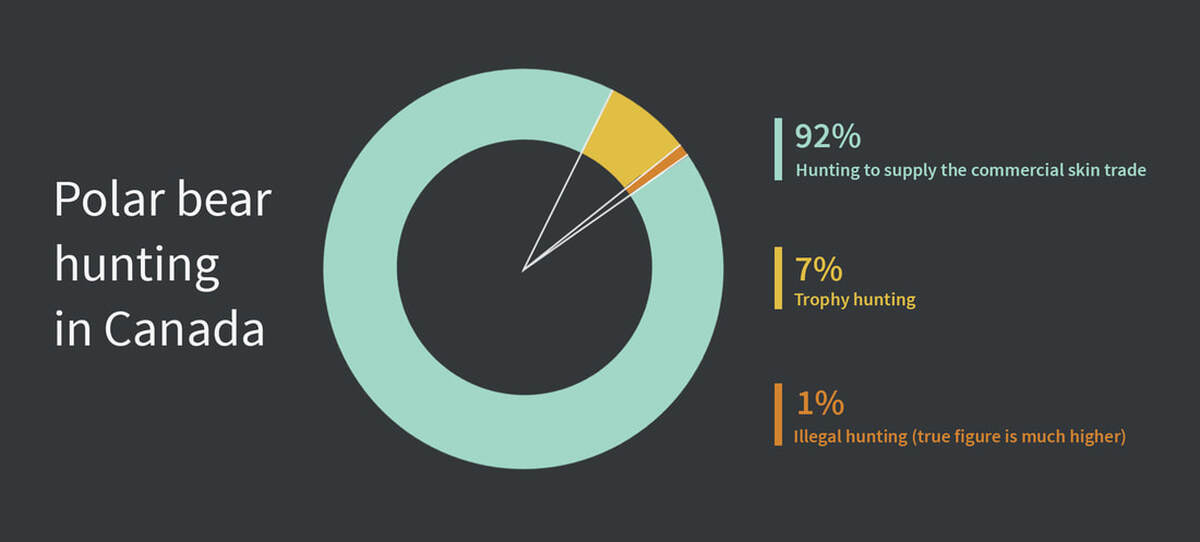

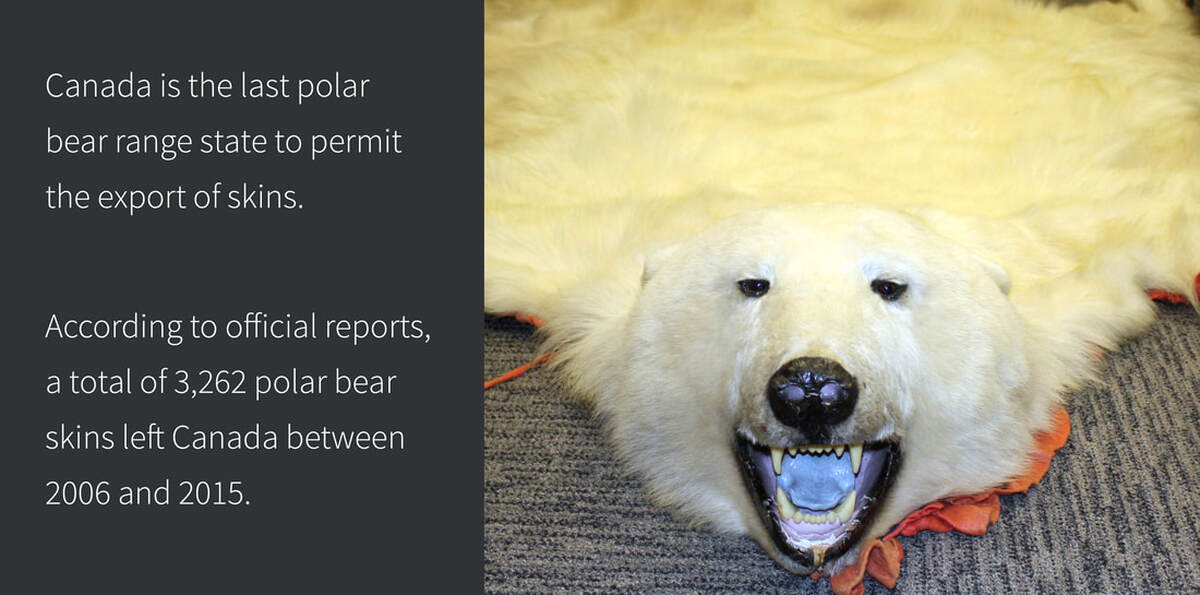

European, Russian and American hunters significantly impacted several polar bear populations from the 1600s right through to the mid-1970s. Change came when the Soviet Union made both native hunting and trophy hunting of polar bears illegal in 1956. The United States banned hunting polar bears for trophies in Alaska in 1972. A year later, Norway followed the Russian example of banning all forms of polar bear hunting. Greenland banned the export of polar bear skins in 2008. Canada is the last polar bear range state to allow the export of polar bear skins and trophies. In other words, all polar bear skins that are traded legally today originate from Canada.

All Canadian polar bear kills are carried out or facilitated by indigenous hunters, who can keep, trade skins to international buyers through intermediaries, such as provincial or territorial governments. Today, most native hunters chose to sell their skins for cash. Part of their quota can also be sold to non-native or foreign trophy hunters with native hunters acting as guides. Thus, for many indigenous hunters, traditional subsistence hunting has turned into a commercial activity that is driven by the lure of high skin and trophy prices on the international market.

Canadian sets hunting quotas for each of the 13 polar bear subpopulaltions across its territory. In doing so, the government claims to ensure the sustainability of polar bear hunting in three declining subpopulations, as well as in five for which neither population sizes nor trends are known. Equally worrying is the fact that the Canadian government supports polar bear hunting and actively promotes the international trade in polar bear skins, including in China. In November 2018, the government owned company Fur Canada courted Chinese buyers with an exhibit at the China International Import Expo in Shanghai for the first time. Fur Canada's website also offered Chinese online buyers the opportunity to conduct a purchase in their own language.

According to data collated by the UN Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Fauna and Flora (CITES), Canada reported the export of 3,262 polar bear skins between 2006–2015 at between 185 and 488 skins a year.

All Canadian polar bear kills are carried out or facilitated by indigenous hunters, who can keep, trade skins to international buyers through intermediaries, such as provincial or territorial governments. Today, most native hunters chose to sell their skins for cash. Part of their quota can also be sold to non-native or foreign trophy hunters with native hunters acting as guides. Thus, for many indigenous hunters, traditional subsistence hunting has turned into a commercial activity that is driven by the lure of high skin and trophy prices on the international market.

Canadian sets hunting quotas for each of the 13 polar bear subpopulaltions across its territory. In doing so, the government claims to ensure the sustainability of polar bear hunting in three declining subpopulations, as well as in five for which neither population sizes nor trends are known. Equally worrying is the fact that the Canadian government supports polar bear hunting and actively promotes the international trade in polar bear skins, including in China. In November 2018, the government owned company Fur Canada courted Chinese buyers with an exhibit at the China International Import Expo in Shanghai for the first time. Fur Canada's website also offered Chinese online buyers the opportunity to conduct a purchase in their own language.

According to data collated by the UN Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Fauna and Flora (CITES), Canada reported the export of 3,262 polar bear skins between 2006–2015 at between 185 and 488 skins a year.

Polar bear hunting quotas: How Canada is trying to square the circle

Canadian polar bear quotas for native hunters are set by provincial and territorial authorities. But instead of being based on scientific population assessments, quotas also take account of “traditional knowledge information” and aboriginal subsistence requirements. Because this is true even when these approaches support conflicting courses of action, it is easy to see how this can quickly push polar bear hunting beyond sustainable limits.

If Arctic communities are growing, are socioeconomically disadvantaged and become dependend on revenue from the sale of polar bear skins and trophy hunts, setting quotas that are not rooted in science is a recipe for disaster. And this is exactly what's happeming. Canada’s Inuit population grew by almost 30 percent between 2006 to 2016. Around 20 percent of the population were affected by poor and crowded housing, and between 20 and 52 percent of those aged 15 years and older had experienced food insecurity during the previous 12 months. From a social justice perspective alone, it is clear that Canada must find alternative ways to uplift the socioeconomic conditions of its growing indigenous population. Placing this burden on polar bears invites a tragic outcome for Canada’s indigenous communities as well as its polar bears.

Polar Bear Hunting in Western Hudson Bay

The history of how polar bear quotas are set in Canada's Western Hudson Bay subpopulation illustrates this problem. In response to a low population estimate for this declining population, the hunting quota for Nunavut hunters in Western Hudson Bay was cut from 58 to 38 polar bears for the 2007–2008 huntimg season. The following year, the hunting quota was further reduced to just eight bears. This small quota was unpopular with native hunters, and just three years later the Nunavut government raised the number of polar bears that could be hunted back to 21. The Polar Bear Specialist Group of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (PBSG) - a group of international experts - considered a quota of even eight bears to be unsustainable. The PBSG had strongly opposed the renewed quota increase and expressed concerns that the Western Hudson Bay subpopulation was likely to decline even in the absence of any hunting. Unpersuaded by the scientists' advice, the government of Nunavut not only ignored it, but raised the 2012–2013 hunting season's quota by a further three bears from 21 to 24. Ultimately, 31 polar bears were killed, followed by another 36 in 2014. This time the IUCN PBSG voiced even stronger concerns, but once again the experts' advice fell on deaf ears. Instead, the hunting quota was set at 28 polar bears for 2016 and 34 for the 2017–2018 hunting season.