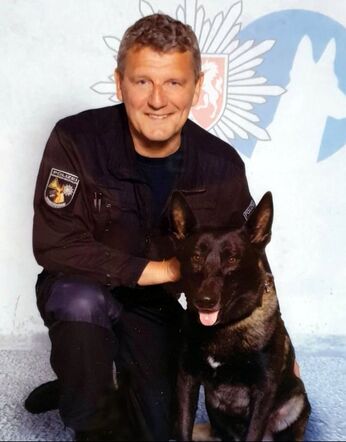

SWEN BUSCHSwen is a man with a fair amount of bite and there is not a shred of doubt that his heart belongs to dogs. Swen began to turn his passion into a profession from an early age and has worked as a police dog handler and trainer for 28 years. More recently, Swen started to share his expertise further afield to help train antipoaching units in Kenya and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Now he is joining People for Nature & Peace to help maintain and build our wildlife protection sniffer dog unit in India. My life with sniffer dogsI was first introduced to handling and training dogs in my teens because my dad used to breed Alsatians. I led my first dog in a test when I was 14 years old. I spent every minute I could on the dog training ground where I met a lot of professional service dog handlers from the police, customs services and the military. My mind was soon made up that I too was going to join the police after graduating from high school. And in 1981 the time had come. However, after I had completed my training in Hamburg, I was assigned to the police department without a dog. While serving as a police officer without dog, I continued to participate in many championships with my own dogs. I was also involved as a protection service helper decoy - the one who gets to deal with the pointy end of the dog - in different competitions right up to world championships. In 1992 I got my first service dog. His name was Rudi and he was a loyal and reliable companion during my time at S.W.A.T. Hamburg. Following my time with the special unit, I became an official service dog handler. My first dog's name was Zeus. Zeus was a competent narcotics dog but sadly cancer took him away far too young. He had been a fantastic dog and I will never forget him. In 2002 I followed the offer to change the federal state and became a trainer in the service dog department of the police of North Rhine-Westphalia. I became specialized in detecting explosives but worked there in different roles until 2008. The "mantrailing" project also happened during this time, which gave me the opportunity to train and lead three dogs operationally in action. In early 2009 I was transferred to work as a dog trainer and the handler of the explosives detection dog Uli at the police headquarters of the city of Essen. Because of my expertise in people tracking, Dr Marlene Zähner from Switzerland contacted me to help her set up the Congo Hounds in the Virunga National Park in DRC. I gladly accepted and traveled to the Congo several times since then. But because of the difficult political situation, I have not been back for some time now, which is a shame. Training the Congo Hounds in the Virunga National Park, DRC, to protect endangered mountain gorillas Besides training police dogs I have been working with the Belgian Malinois male Santos for several years. Santos and I are partners against crime. We live and work together as a team with a strong mutual bond and understanding. It's an honour for me to train wildlife protection canine units around the world, and I am happy and excited to support People for Nature & Peace as its K9 technical advisor in India from now on. Maybe it will help to make the world a little better. Let's go... Swen and Santos PNP says: Welcome to the team Swen! We can't wait to get stuck in with you.

0 Comments

9/6/2020 David Jamilly - The beginning or the end for endangered species: Will the post pandemic world be a kinder place?Read NowDavid JamillyDavid Jamilly has been involved in social projects since his teens. In 1977, he set up the Pod Children's' Charity, which has provided live entertainment for over a million hospitalized children in the UK. David is involved with various social projects in Bhutan and numerous causes in the UK. He is the founder and CEO of Kindness UK since 2011; the country's benchmark organisation for promoting the positive value of kindness in day to day life. Kindness UK has recently expanded its focus to promoting kindness in relation to animals and the environment. Here is why.Will the post pandemic world be kinder?In times of crisis, the human psychological reaction is to think local as opposed to global. What this means is that funding from the West for many wildlife preservation projects has dried up during the pandemic period, with dire consequence for many species. Conservation projects often protect species from local populations which hunt primarily for need, not greed. However, it is greed that is ultimately the driving factor; the greed of those who already have enough, which fuels the need of the locals who end up as exterminators. This same insidious cycle applies to the natural world and the destruction of the environment and its natural resources like water and forests. Unfortunately the disparity between rich and poor globally has never been more exaggerated, and it is this imbalance that needs to be redressed as quickly as possible for the protection of threatened animals. Although the air smells sweeter as carbon emissions are temporarily reduced, there are day by day less free animals around to enjoy it. During the pandemic we have seen lots of amazing local kindness initiatives spring up. Examples include voluntary food projects, key worker support and organisations that provide care for the vulnerable; as well as wide enhanced neighbourhood bonhomie and sharing. Some of this will continue in one form or another and the world will indeed be a kinder place for a period in the direct aftermath of the crisis. However it will unfortunately take a much longer time until attentions are re-focused on the plight of endangered species. This most certainly highlights the crucial need to support projects like People for Peace and Nature and others now, as their work takes on increasing importance both on local activation and on lobbying/awareness levels. In terms of kindness itself; it cannot be taught as easily to adults as it can to children. Young minds yearn for fresh information and assimilate positive values readily. With adults it is more a case of reprogramming or epiphany. Another feature of kindness is that it has more impact on a bottom up basis rather than a top down; but nevertheless it is ultimately through global mass kindness that we can effect enduring positive societal change. We are privileged to share this beautiful planet with so many wonderful species and it is imperative that we urgently turn our thoughts towards them before it is too late. Nikki BothaVegan chef and civil society activist [because no civil society treats animals the way we do]. She resides in Cape Town, South Africa with her husband and her blind cat Cassie, also known as Snucky Puckie Pookie Pie Lovebug McFoefel Face. On Being A Vegan ChefI am an accidental chef. A career in cheffing was the last thing in the world I would have ever considered. I hated cooking. With a passion. I wanted to be the writer of the next great novel, an Oscar winning actress, a model, a nun, a circus clown, a fighter pilot, a teacher – or whatever career took my fancy at any given point in time. A chef? NO with a capital en oh. Not only did I loathe spending time in the kitchen, but I once made food so bad that it made my sister’s friends cry [true story]. Even my home ec teacher told me that the only hope for me was to marry a wealthy husband. She ended off with ‘I will pray for you.’ But life doesn’t always take us where we want to be, but where we need to be. In 2013, I was invited to join up as a volunteer deckhand on a conservation ship. At the time of joining, the ship was in dry dock for repairs and the only crew at that point was the captain, the engineer and I [more crew would eventually join]. It kind of fell on me to do the cooking. It was almost enough to make me quit and I spent the first few nights in my bunk crying, feeling like the biggest failure in the world. I had absolutely no idea how I was going to do this for three months. I considered giving up. My culinary skills included burning toast and either undercooking or overcooking rice. That was pretty much the extent of my talent in the kitchen. My pride, however, was stronger than my burning desire to quit. So I sucked up my pity party and decided that I was going to at least give it my best shot. I suspected that the Captain would sooner rather than later send me back to deck to paint or fiberglass or grind or sand. But at least I could say I tried. I started to ferociously read every single cookbook, every single recipe I could get my hands on – obsessively. Like other people read novels, I read cookbooks and recipes every free second I got. And it paid off. As it turned out, I was apparently really good at making food. I may not have a creative bone in my body [despite my mother being an artist], but I found that my ingredients were my paint and my plates were my canvasses. I fell head over heels in love with, of all the things in the world, cooking. After my three month stint on the ship, I headed back home. A friend of mine had just opened up our city’s first all vegan restaurant and asked me to be her head chef. I was so gobsmacked, you could have knocked me out with a wet feather. The only experience I had was cooking a set breakfast, lunch and dinner for a maximum of 8 people. I had no restaurant experience and knew more about rocket science than I did about running a commercial kitchen. I had ‘faked it till I made it’ so far and I was willing to push the envelope a little further, so I accepted the position. I took to it like a duck to water. The challenge of communication and managing a brigade; and the rush of text book timing was like a drug. I couldn’t get enough of it. At the end of each day I was so tired I couldn’t remember my own name, but the high I felt made me feel like I could conquer the world. I was in my element. My kitchen and menu went on to win local and international awards. I ended up cooking for local and international celebrities; heading up catering for large, high profile international events; having recipes published and running the galleys on two more conservation ships. But I soon came to realize that there was a lot more to being a vegan chef than just winning awards or creating best selling dishes. I had a tremendous responsibility on my hands. Veganism was still relatively new back then. Vegetarianism was still seen as ‘quirky’ and just the right amount of hippie, but veganism was a concept which discombobulated most people. It is only in the last 4 years or so that veganism became a mainstream concept. Mention vegan food and most people thought [and still do] that it involved munching on carrots and licking cardboard as a treat. As a vegan chef, I have a responsibility to crush that notion like I crush tempered cumin seeds in my mortar and pestle. As a representative for the animals, the food I serve has to convince people that you don’t have to sacrifice taste, texture, gastric pleasure and/or health if you omit animal products from your plate. One meal could literally be the difference between life and death for an animal. A substandard dish can put people off veganism forever and perpetuate the myth that vegan food is bland, unappetizing, unhealthy and boring. A top quality dish is the best and quickest way to advocate for animals. All this being said, what I love more than being a vegan chef, is teaching people HOW to cook vegan. I want each and every person to be empowered to cook vegan at home and inspire others to explore the fantastic, creative and delicious world that is kindness and compassion. Because the more people know, the more they are empowered, and the more they are empowered, the more they can do. Or in this case, the more animals they save. |

|

CONNECT WITH PEOPLE FOR NATURE & PEACE

|

MAKE A GIFT TO NATURE

|

|

All rights reserved © 2022 People for Nature & Peace

|

Registered charity no. 1183764

|